Attending the Internet Governance Forum - Stakeholders

(This is a post in a series about attending the Internet Governance Forum 2023 in Kyoto.)

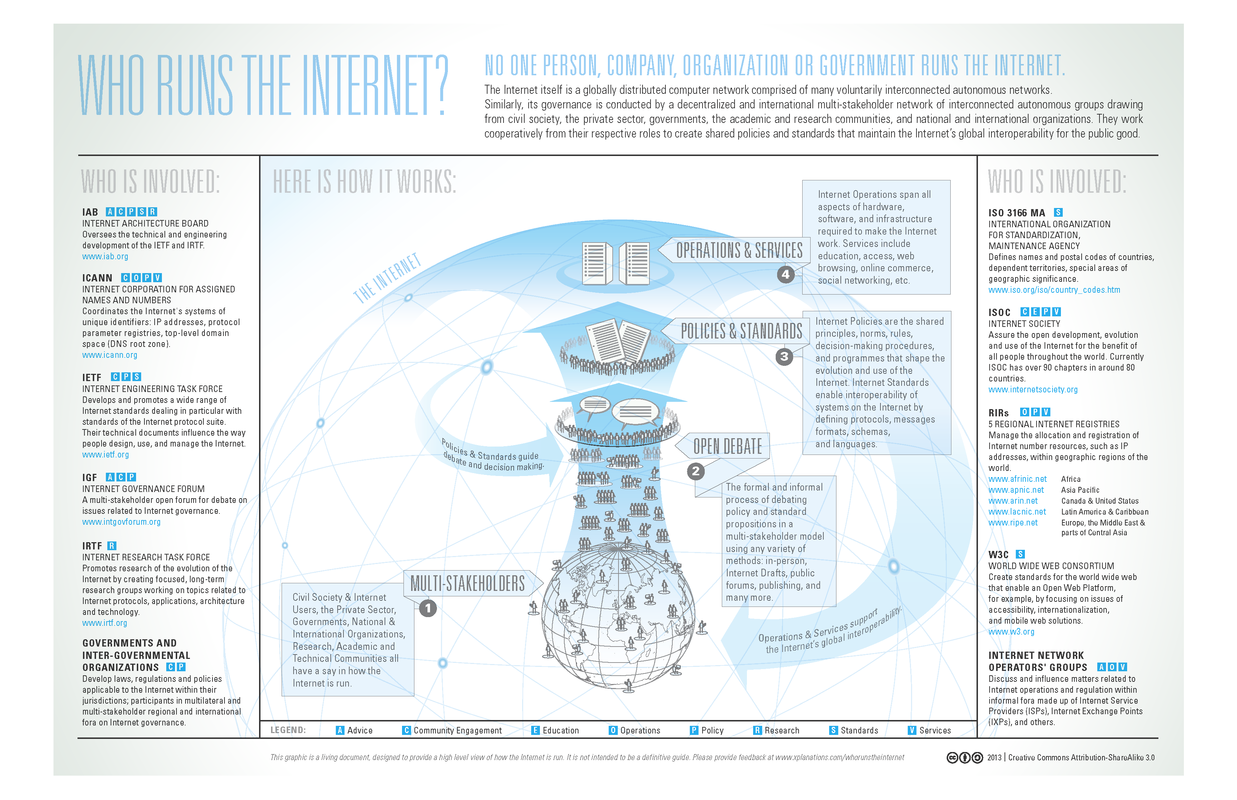

To describe where the Internet Governance Forum fits in terms of internet governance, we have to also describe the other stakeholders in the system. Internet governance is polycentric. The IGF is just one part of a network of stakeholders that hold influence over how the internet works. Its key mandate is to bring various stakeholders together in a forum to discuss public policy, which is a key differentiator from other technology fora.

Being an initiative of the UN, you might think that nation states are the only important stakeholder, but the IGF was designed from the beginning with multistakeholderism in mind. In fact, multistakeholderism was probably one of the top three topics discussed during the week in Kyoto, possibly triggered by the actions of China at previous meetings as it tried to use its influence as a big stakeholder to try and force internet governance into mere bilateralism (You can read a little background here. I asked people who were at the meeting in Ethiopia who told me some of the stunts being pulled by the Chinese contingent there. This year it seemed pretty quiet to my eyes.).

The IGF holds dear a key belief of a singular, unbroken, and supranational internet. Thus it tries to include a broad number of regional and international actors to come and weigh in on important debates. Let’s break down the organization of the IGF first, and then connect that up to the wider web of who else is involved in governing the net.

Breaking down the IGF

First you have the MAG, or Multistakeholder Advisory Group, which is made up of 56 representatives from various stakeholder groups. They meet a few times a year in order to execute the annual meeting (you can see the list of current MAG members here). The MAG is supported by the Secretariat, which is the UN staff based out of Geneva that support the activities of the MAG. This group of just 6 people are the only full-time staff of the IGF, and are ultimately responsible for running a global hybrid conference with 11,145 registrants. 😱

Beyond those two main parts, there are something called NRIs, or “National, Sub-Regional, Regional and Youth IGF initiatives.“ This is a wider network of smaller fora organized either geographically or around a specific theme, holding their own annual meetings. There about 123 regional and national IGFs recognized by the global IGF in Geneva (here is Canada’s and Japan’s). Youth Initiatives can be part of regional IGFs or independently organized. They are the IGF’s way of capacity building by increasing youth participation in internet governance.

The stakeholder community

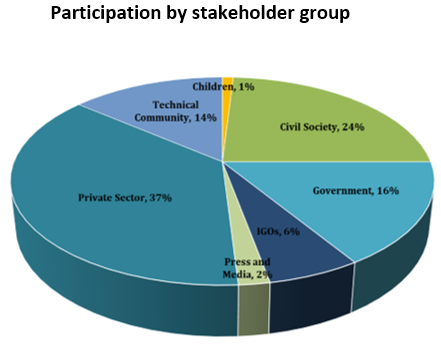

So, the MAG, Secretariat, and NRIs engage with other stakeholders, bringing them to the table for policy discussion. The IGF groups stakeholders into the following five categories:

- Government

- Intergovernmental Organization

- Civil Society

- Private Sector

- Technical Community

When you apply to attend, you must identify yourself as coming from one of those groups. When I looked at the participants list I counted about 4000 organizations being represented. That is from 178 countries. So, I won’t list all the stakeholders, but I can give a few examples to give you an idea:

- For Government there are many lawmakers and representatives of agencies from different countries. A politician from Nigeria asked some incisive questions at a DNS session I was in, and I had a good hallway chat with a person from USAID.

- Representatives from the UN, the EU, ITU etc are in the Intergovernmental Organization category. I was in a couple sessions with an OECD policy analyst working on Data Governance and Privacy who I liked.

- Civil Society includes human rights NGOs and other advocacy groups. The Internet Society, Wikimedia Foundation, Access Now, and the Green Web Foundation. I was very impressed with the well-spoken Anita Gurumurthy, ED for IT for Change in India. Many of these people spoke up about the IGF being held in Saudi Arabia next year, feeling like this stakeholder group is being shut out.

- The Private Sector group captures companies and interested individuals. I registered as this group. But it does contain large corporate interests. Attendees from Microsoft, Google, Netflix, and Meta were there. The head of public policy Cloudflare gave a couple of good sessions, and the Global Product Policy at Mozilla was very well-spoken.

- The final group – Technical Community – is a big one which includes reps from Standards Developing Organizations (SDOs) like the IETF and W3C, professional orgs like IEEE, as well as important internet organizations like IANA which delegates IP numbers to the five Regional Internet Registries who coordinate via the Number Resource Organization (NRO). There was a large ICANN contingent in Kyoto, and booths from various operator organizations such as ISPs, IXPs, and Telcos like NTT. However, I felt that the technical presence was a bit lacking. More about this in another post.

One other group that was well-represented was academia. There were many scholars and students there, especially from Kyoto which is a college town.

Source: IGF 2023 Participation and Programme Statistics

So, who does really run the Internet?

An heroic attempt at explaining how no single entity runs the internet, from the Wikipedia article on internet governance.

Internet governance is continuously evolving as we try and solve complex problems as the internet not only expands in usage across the world, but brings new problems due to scale. Since the first event in 2006, IGF participation has grown, especially with the ability to attend virtually. Here are the registration numbers for the last 10 years (includes both in-person and online):

- Bali 2013 - 2,000

- Istanbul 2014 - 3,694

- João Pessoa 2015 - 2,130+ (couldn’t find online attendance stats)

- Jalisco 2016 - 4,000

- Geneva 2017 - 3,680

- Paris 2018 - 4,400

- Berlin 2019 - 5,679

- Online 2020 - 6,150

- Katowice 2021 - 10,371

- Addis Ababa 2022 - 5,120

- Kyoto 2023 - 11,145

More and more stakeholders are taking an interest. Countries may make the laws and look for input (or don’t) from other stakeholder groups, but they aren’t necessarily the final stop on the power spectrum. For example Mark Nottingham points out (in an excellent post!) that what standards orgs do is a kind of ”architectural regulation” which:

… sits alongside other modalities of regulation like law, norms, and markets. Where the FTC uses law, the IETF uses architecture – shaping behaviour by limiting what is possible in the world, rather than imposing ex post consequences.

That makes Standards Development Organizations another kind of Transnational Private Regulator (TPR).

There are many ways to get your say and how we govern the internet is not set in stone. We still have another 2.6 billion unconnected, the ongoing threat of a splinternet, geopolitics and geoeconomics amongst other influencing factors. And we need need NEED to have this communication and coordination infrastructure up and running if we are ever to work together globally in defeating the biggest existential threat on the planet: the climate crisis. Ultimately, this is why I find the IGF process so fascinating and intend to become a more engaged stakeholder.

#IGF2023