Vancouver’s “Powerbroker” — a sort of review of “Becoming Vancouver”

On a pleasant summer’s eve, as the setting sun lit the tops of classic New York skyscrapers, I sat in Madison Square Garden Park in Manhattan’s Flatiron District. Ultimately it was here that lead me to pick up Daniel Francis’s Becoming Vancouver, a quick history of the city of a city that has been central to my whole life.

You see, while watching the crowds in the Manhattan park during my trip to New York last August (photos) I started listening to 99% Invisible’s breakdown of The Powerbroker, a veritable tome by celebrated author Robert Caro which chronicled the career of power-hungry urban planner Robert Moses, a man who transformed New York City over a 40 year career, and certainly not all for the good. The podcast series is excellent and I have been recommending it non-stop. It really is a sordid tale with many generalizable lessons on leadership, ambition, and justice. Once 99pi concluded the series they had a Breakdown of the Breakdown episode when they were asked by listeners: are there any other Robert Moses-like figures in other cities?

Looking for a Moses

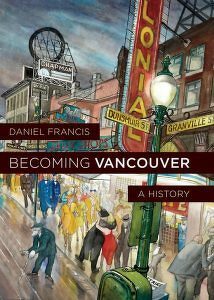

Which brings me to Daniel Francis’s excellent book Becoming Vancouver. Weighing in at less than a fifth of Caro’s Powerbroker, and covering three times the timespan (from the Musqueam meeting the first Spanish explorers to the havoc wrought by COVID), it is a breezy read filled full of the kind of content you expect in a city biography: factoids about geography, place name etymology, maps showing the expansion of the city, funny anecdotes, serious incidents, and in general the book simple answers the perennial question “Why is our city like this?”

What a great reflection! Why is our city the way it is? It is really important that we know the history and stories of our shared community. It is what puts us on the path to being citizens, rather then mere passive consumers.

Some related posts about a previous city of mine:

New Yorkers have much love for their city, but also a multitude of complaints (as you will hear if you pick up the 99pi podcast) — many of which can be tied back to the urban planner Robert Moses.

Vancouver certainly has its share of inconveniences, inconsistencies, and hypocrasies. So I set out to find if Vancouver had it’s own Robert Moses.

Daniel Francis has written a number of works on the history of Vancouver. Reading Becoming Vancouver I learned many tidbits of our shared history, for example:

- Jericho used to be known as “Jerry’s Cove” named after logger Jeremiah Rogers

- On Jan 1, 1922 traffic was switched from the left (British-style) to the right-hand side of the road

- 1400 citizens died in WWI

Mostly it was interesting to see a few of the “red threads” that have strung their way throughout Vancouver history since the beginning: the role of real estate speculation, the city’s battle with drugs, and race relations. Throughout the book are constant tales of housing shortages, police incompetence, and just endless incidents of racism against every sort of non-white person regardless whether they were here before or came after the British settled the area. Francis does an excellent job engaging critically with the history. Furthermore he also weaves another thread:

the always present fault line in Vancouver’s history between the globalists, who promoted a vision of unlimited growth, and the localists, who preferred to emphasize their version of liveability.”

There is tension between preserving Vancouver’s natural beauty and pushing forward it’s urban development.

The coming of a powerbroker

Like any urban biography Becoming Vancouver is features vignettes of a number of politicians, planners, and all-round characters, but the one that jumped out to me was Gerald Sutton Brown described as was “the most powerful bureaucrat in the city” during the 1950s and 1960s.

Born in Jamaica, Sutton Brown was educated in Southampton, UK and ended running the county planning office that included the cities of Manchester and Liverpool. He came over to Canada in 1952 to become Vancouver’s first chief planner.

You can learn more about the background of Sutton Brown and his impact on the city in this video by former Vancouver Mayor Sam Sullivan:

While there are some great visuals and some interesting facts, that video is particularly hagiographic, pushes a market-based agenda, and completely ignores the problematic aspects of Sutton Brown’s policies.

Daniel Francis’s book treats the Great Freeway Debate of 1967 with a more critical eye. Sutton Brown’s “Project 200” proposed a waterfront freeway cutting through Vancouver’s Chinatown and Hogan’s Alley, the core of Vancouver’s Black community. Sam Sullivan’s video does not question why it was stopped. The answer is the story of the Chinese community organizing and fending off the freeway plan, saving their houses. This case is important, and in fact is the final study in the book Moved by the State which covers how “the Canadian government relocated people, often against their will, in order to improve their lives” during the 1950s to 1970s. Although their protest was successful, it was not complete. Hogan’s Alley, Vancouver’s small black neighbourhood, was razed in the late 1960s in the name of “urban renewal”, and the Georgia Viaduct still stands in its place. (Check this out if you are interested in learning more about Hogan’s Alley).

God, or just a mid-century white dude

Was Sutton Brown a “powerbroker”? I could find no Caro-like biographies of the man, but I did come across this paper that paints Sutton Brown in a most Robert Moses-like light: “Is Sutton Brown God?”: Planning Expertise and the Local State in Vancouver, 1952-73” The paper’s title comes from a protest sign during the Great Freeway Debate of 1967. Sutton Brown, the “firm-handed dictator of city services” had “predetermined the freeway route without ever engaging the political process.” This will sound entirely familiar to those that know the legacy of Robert Moses in New York.

Furthermore:

Between 1967 and 1972, the public, aldermen, provincial politicians, academics, the press, and elements within the civic bureaucracy repeatedly criticized the role of planning expertise in the affairs of the local state. “Who is really running the city?” was the headline that summed up sentiment.

After a more than 20 year long career, Sutton Brown resigned his position (some said before he could be fired).

The Province, no friend of TEAM [a political party], wrote that Sutton Brown’s departure was a “guillotine job,” citing his twenty-one years of “brilliant service,” even if he was “an aloof dictator.” Similarly, Alderman Hardwick said that he did not blame Sutton Brown for being the real mayor of Vancouver as council had pushed the role on him instead of doing its job.

I am not sure if Sutton Brown is was a powerbroker in the mold of Robert Moses, or was just a powerful white British man during the 1950s, doing what he do. But I do think his case is worthy of a more indepth investigation. If Daniel Francis doesn’t want the assignment, maybe 99pi will take it? 😉